Learning Program Plans with Jigsaw

An important step in developing programming expertise is learning programming patterns. These patterns represent reusable partial solutions to common programming challenges, such as the accumulator pattern for summing values (and other sequential variable updates), or the filter pattern for operating only on values that match a condition.

Research suggests that students can benefit from learning these patterns explicitly, and practicing how to compose these patterns into a complete solution.

Jigsaw

Jigsaw is a learning environment for practicing the pattern composition process, allowing students to see the commonalities between problems, and learn the individual patterns in more depth.

Jigsaw allows students to plan out the solution to a program using patterns before going on to implement it. By separating planning from implementation, the student can focus on learning each skill individually.

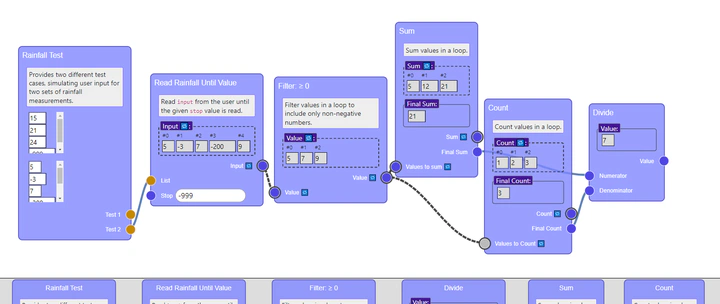

For example, the animation below demonstrates constructing a solution to a simplified version of the classic Rainfall problem using Jigsaw. Students are given a series of rainfall measures and and asked to compute the average of the non-negative readings.

Programming Pattern Blocks

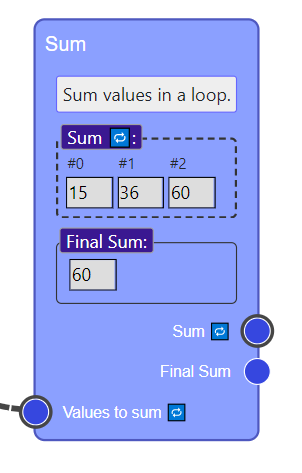

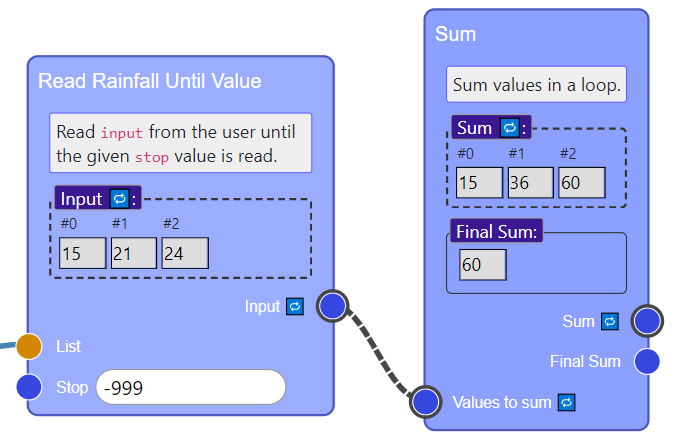

In Jigsaw, individual programming patterns are represented as blocks. One common pattern is summing sequential values (e.g., in a list or read from user input). Jigsaw has a corresponding Sum block. Given the input [15, 21, 24], the block looks like this:

In imperative programming, this block roughly corresponds to the following python code:

def sum(values):

total = 0

for item in values:

total += item

return total

The Sum block shows both the final sum (60) and the intermediate values that sum takes throughout the iteration (15, 36, 60).

Patterns != Functions

In the Sum example, it is easy to assume a pattern is similar to a function, but many programming patterns don’t fit easily into functions (at least in imperative languages). For example, another common pattern is reading values from input until a given value is reached, as in this python code:

answer = input("Enter a number of 'stop' to finish:")

while answer != "stop":

answer = input("Enter a number of 'stop' to finish:")

# Do something with the answer

While it is possible to encapsulate this pattern in a function, doing so may be difficult or unintuitive for early programmers. Additionally, this pattern is often interleaved with other code. For example, to sum the user input, we might write:

total = 0

answer = input("Enter a number of 'stop' to finish:")

while answer != "stop":

item = int(answer) # convert to an int

total += item

answer = input("Enter a number of 'stop' to finish:")

# Do something with total

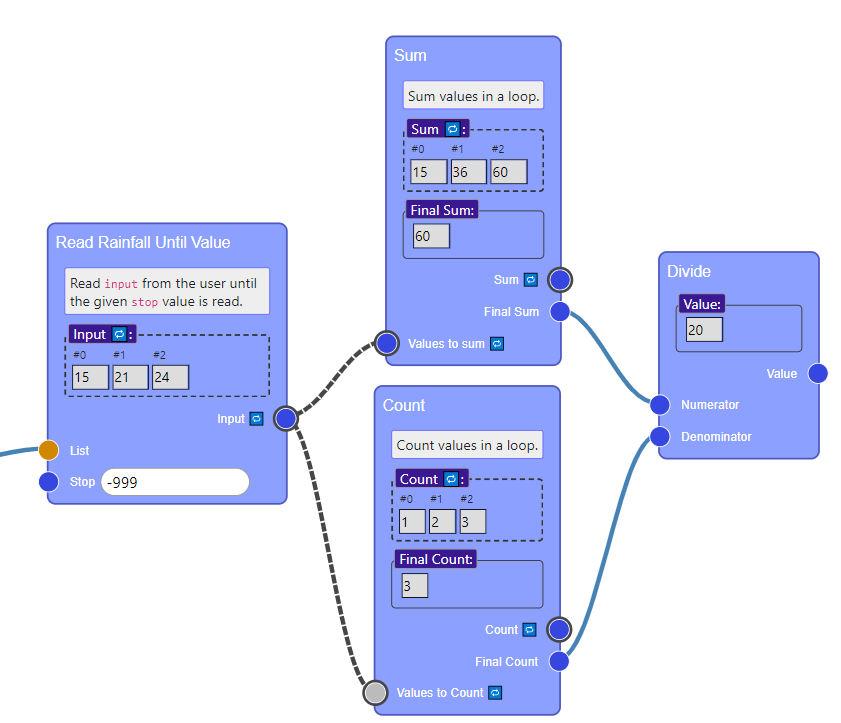

While these two patters are closely interleaved, we still want the student to recognize them as separate patterns that could be reused in other contexts, such as summing without user input (e.g. summing a list), or reading input without summer (e.g., finding the minimum value given by the user). Jigsaw makes this distinction clear, while also showing how the patterns can be composed to solve the problem. In this case, we simulate the user input: [15, 21, 24, stop].

The Power of Composition

We can add another pattern to get most of the way to a solution to the Rainfall problem:

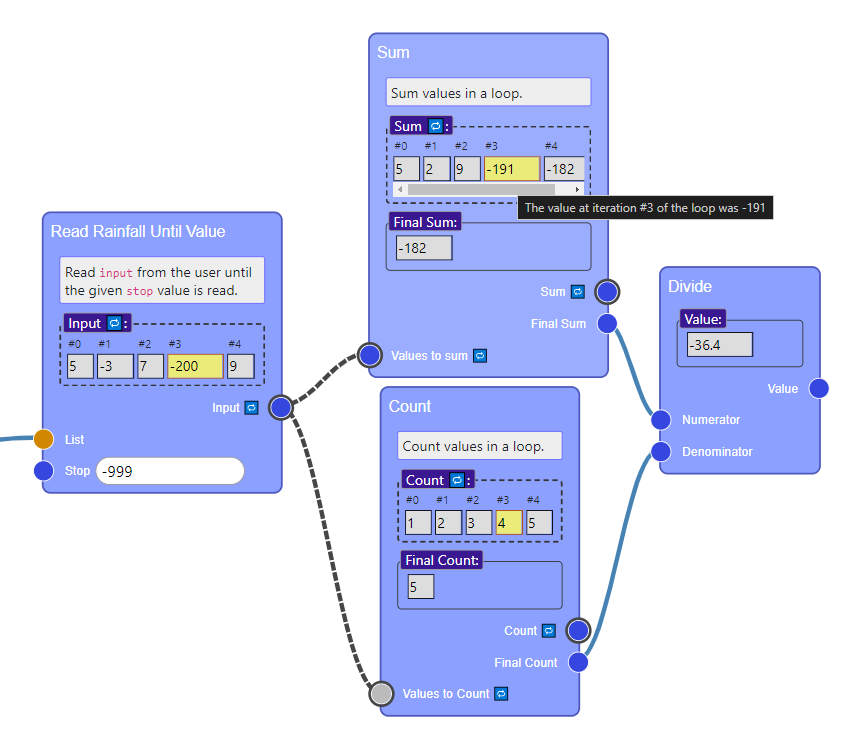

However, remember that in the Rainfall problem we’re supposed to ignore negative readings. So our current approach won’t work for more complex input.

Jigsaw reveals not only that this test case fails, but also why. IF we look at the value for Read Rainfall Until Value or Sum, we can see where in the loop the input was negative, and hovering over that item shows the corresponding values in other blocks.

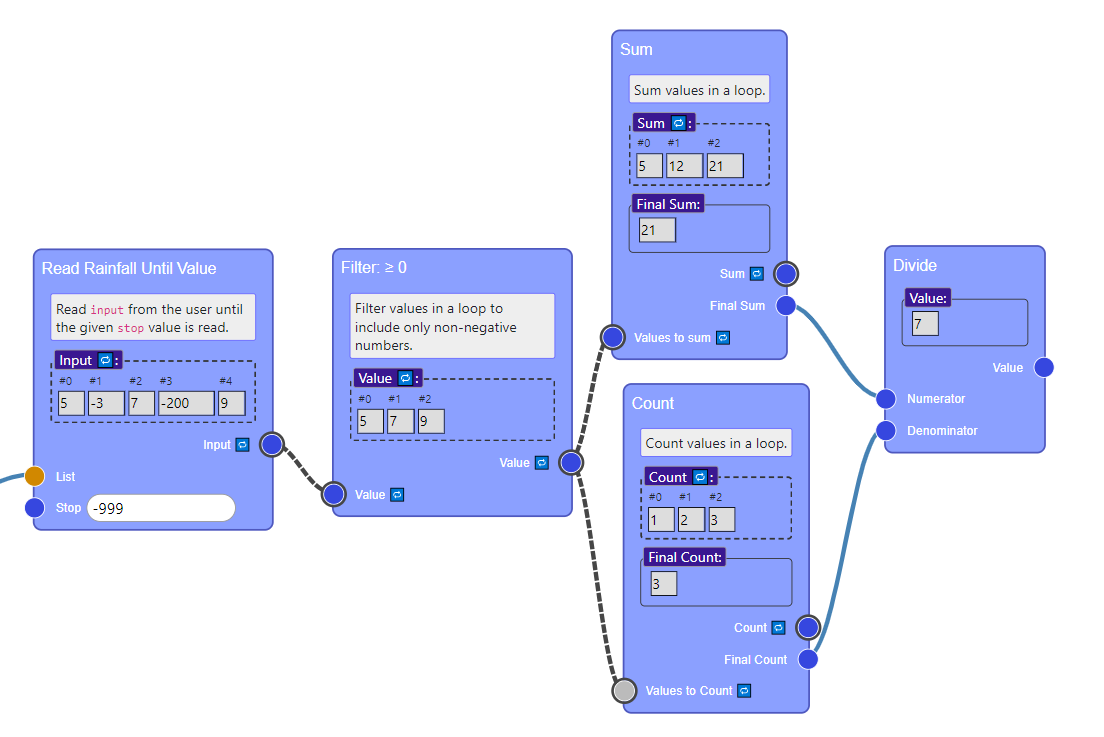

We can that problem with a Filter pattern:

At this point, we’re ready to convert out plan to code. Jigsaw doesn’t specify what the implementation needs to look like, but one version could be something like this:

total = 0 # Sum

count = 0 # Count

answer = input("Enter a number of 'stop' to finish:") # Read

while answer != "stop": # Read

item = int(answer)

if item >= 0: # Filter

total += item # Sum

count += 1 # Count

answer = input("Enter a number of 'stop' to finish:") # Read

average = total / count # Divide

There’s still plenty of work for the student to do to figure out the implementation, but now they have a clear plan to do so, and an intuitive sense for how these patterns work and work together.

Live Editing

The patters in Jigsaw aren’t hard-coded. Its output is computed live using an internal interpreter.

This allows students to try other inputs and solution plans, and to experiment with the plan blocks and their approach.

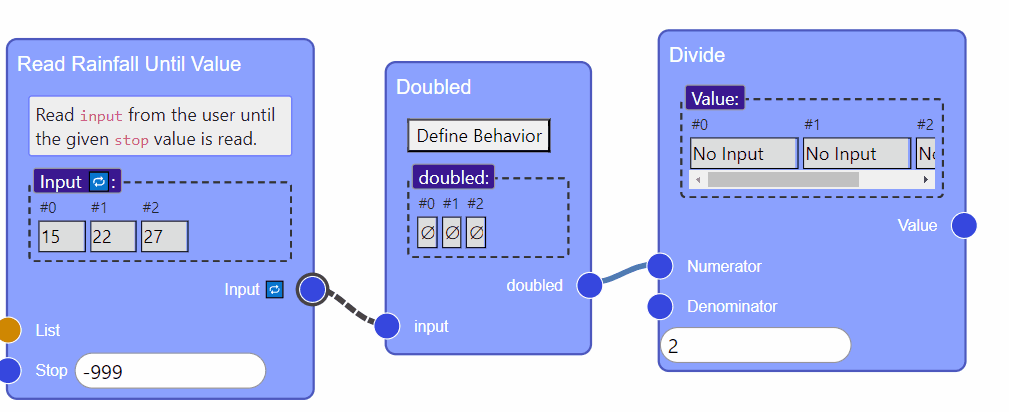

Student-defined Patterns

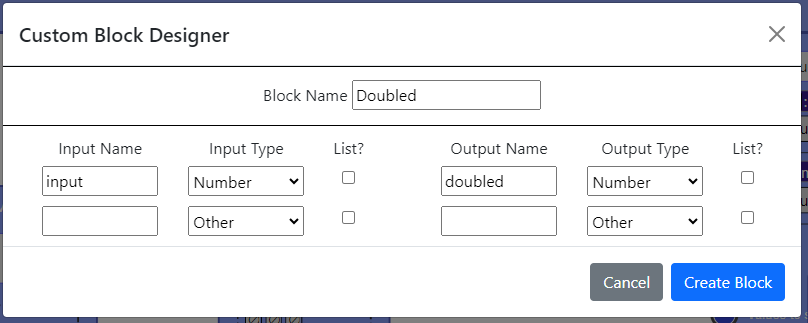

If students want to use patterns that aren’t defined by Jigsaw in their plans, they can define their own pattern, specifying the types of its inputs and outputs:

Then, when they use the block in their plan, they are asked to specify the outputs of the pattern, for each of its inputs. Afterwards, they can use their new plan block in a larger plan.